Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum: Sweet Home (of motorcycles), Alabama

There are moments on the road when emotion overrides expediency. I was in Nashville with a roadmap spread out over the hood, tracing the most direct route to Dallas through Tennessee, Arkansas and Texas, when I saw a small icon in Birmingham, Alabama.

Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum, it read. I Googled it. The reviews were rapturous and almost religious in their fervour. One simply said, “If you love motorcycles, this is your Mecca.”

I rerouted at once. Even though it meant a triangular detour through Alabama and Mississippi that added 200 miles to my original linear route.

The dairy magnate who built a temple for two wheels

To understand the Barber Museum is to understand the obsession of one man: George Barber. A successful dairy magnate from Birmingham, Barber was bitten by the racing bug early, competing in vintage racing throughout the 1960s. But his true passion crystallised into something more permanent – a collection that began modestly and metastasised into what is now recognised as the world’s largest motorcycle museum. Not just in America. Not just in the Western Hemisphere. In the world.

The numbers are staggering with over 1,600 motorcycles in the collection, and around 950 on display at any given time. They span from the very dawn of motorised two-wheelers, including those Victorian contraptions that were equal parts bicycle and steam engine, right across to modern MotoGP missiles. Every significant marque is represented: Vincent, Brough Superior, Indian, Harley-Davidson, Norton, Royal Enfield, Triumph, BMW, Honda, Yamaha, Ducati, and dozens more that I had never heard of but suddenly needed to know everything about.

Barber didn’t just want a museum. He wanted a cathedral – a space where the faithful could come to worship at the altar of mechanical beauty. In 2003, the 8,30,000-square foot facility opened its doors: a modernist structure of concrete, glass, and reverence. Attached to it is the Barber Motorsports Park, a world-class racing circuit, where these machines’ spiritual descendants still raucously roar and race.

First impressions: Stopped in my tracks

The building announces itself with industrial humility. No pompous columns or unnecessary ornamentation; just clean lines and enormous windows that flood the interior with bright Alabama sunshine. I paid my admission fees and stepped through the entrance.

And then I stopped in my tracks.

The first thing that hit me was the sheer verticality of the space. Rising before me like some impossible sculpture was a towering vertical rack of motorcycles stacked on illuminated shelves that climbed toward the ceiling like a mechanical Jacob’s ladder. Yamahas, Kawasakis, Hondas, Ducatis – all suspended in space, each one a jewel in a display case. The engineering required to mount motorcycles at such angles – to make them appear to defy gravity while remaining perfectly preserved – is itself worthy of admiration.

But this was merely the opening salvo.

The layout of reverence – and rebellion

The Barber Museum doesn’t organise its collection by strict chronology or geography. Instead, it invites inference. Motorcycles are grouped thematically by manufacturer, or by purpose, or even by aesthetics. I walked from a row of pristine British singles from the 1950s directly into a section devoted to Soviet-era scooters that speak of a completely different motorcycling philosophy.

The transitions are seamless, the juxtapositions deliberate. The museum was inviting me to compare not just engineering, but ideology.

The architecture of obsession

What makes Barber different from every other motorcycle museum I’ve visited is the curatorial ambition. This isn’t a warehouse with bikes parked in rows. This is a museum that’s intended to be theatrical. Motorcycles are displayed at varying heights, angles and contexts. Some sit on raised platforms made of wood that’s been intentionally weathered. Others are suspended in glass cases. Still others form patterns by way of walls of identical models in different colours, or evolutionary sequences showing how a single model changed across decades.

There’s an entire section devoted to racing machines, and here the museum’s layout becomes almost liturgical. I strolled between rows of Grand Prix bikes from the 1960s and ’70s – swoopy, colourful, impossibly narrow machines that men piloted at speeds that were nothing short of suicidal. An AJS from the 1950s, wearing race number 1 – its black tank adorned with gold pinstriping and the AJS logo rendered in Gothic script – sits frozen mid-competition, its golden engine cases gleaming under spotlights.

The windows throughout the museum provide views of the surrounding landscape, enhanced by the lush Alabama greenery that serves as a living backdrop to these mechanical artifacts. The contrast is deliberate: nature in its eternal patience, and machines representing humanity’s restless need to go faster, further, louder.

The respectful gatecrashers

And then there are the cars. Yes, cars. Scattered throughout the museum are automotive icons: a white Corvette, a silver Mercedes-AMG GT, a Shelby Cobra 427 Spec Competition Roadster, a Ford GT. They feel like visiting dignitaries and are respectfully placed – never overshadowing the two-wheeled majority. Barber’s collection includes significant automobiles, but their presence here feels like punctuation marks in a long mechanical sentence, like brief pauses before the motorcycle narrative resumes.

One of the most arresting displays features vintage scooters arranged against those massive windows. Besides Lambrettas and Vespas, there are their international imitators, each one a small poem about post-war optimism, about cities rebuilding themselves one buzzing commute at a time. These may be simple and humble machines, but the two-wheeling revolution they brought about has given them an even more honoured place in history than the exotic racing machines on display nearby.

The deeper wandering

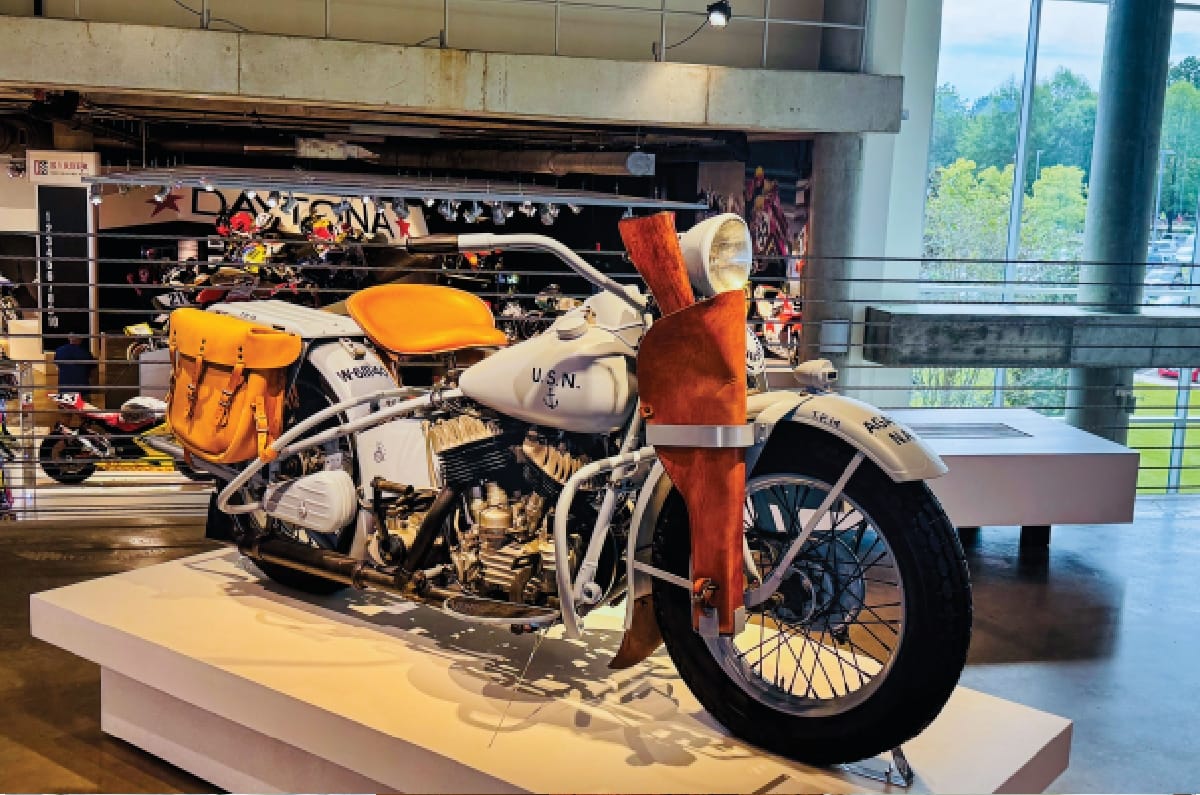

As I moved deeper into the museum, I began to lose track of time. This is its magic and its danger. I had chalked out two hours here, but then I discovered an entire section devoted to military motorcycles. Harleys with U.S.N. stencilled on their tanks, carrying what looked like a wooden rifle stock and military equipment. Time stopped as history beckoned, and I learned about how motorcycles went to war. Two wheelers serving as dispatch vehicles, reconnaissance platforms, and even ambulances.

I also stumbled upon the steam-powered velocipedes; those preposterous Victorian experiments that looked more like elaborate kettles on wheels than motorcycles. The sight gave me goosebumps, because they are the genesis, the beginning of everything that followed.

The museum’s lower level opens into a dining area, and the curation continues even here. Motorcycles line the walls, and racing bikes hang in formation like a mechanical air show frozen in time.

The emotional calculus

What surprised me most wasn’t the scale or the rarity of the collection, though both are extraordinary. It was the emotional response the museum provokes. This isn’t simply about preservation or cataloguing. It’s about passion made tangible. Every motorcycle here represents someone’s dream. It could be that of the designer who sketched the lines, the engineer who made it work, the racer who pushed it to its limits, or simply the commuter who relied on it daily.

Walking through the Barber Museum is like walking through the annals of human ingenuity filtered through our obsession with personal mobility. Here is our need for speed, our aesthetic ambitions, our engineering prowess, our tribal affiliations (Harley vs Indian, Honda vs Yamaha, British vs Italian), and our sheer stubborn refusal to accept that two wheels are inherently less interesting or ingenious than four. By the time I emerged back into the Alabama afternoon, blinking against the sunlight, I had been inside for nearly five hours. My mind buzzed with images: chrome and paint, leather and aluminium, the sweep of a fuel tank, the gleam of an engine case, the purposeful aggression of a racing fairing.

The pilgrimage imperative

If you consider yourself even remotely passionate about motorcycles, the Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum isn’t optional, it’s essential. This is the place where the history of motorcycling has been curated with genuine love and displayed with theatrical brilliance. It’s where you can trace the evolution from primitive steam cycles to modern superbikes in a single afternoon and where you can simply stand in silence and appreciate what humans have created in our eternal quest to balance on two wheels and go faster.

The Unusual Suspects

1964 Royal Enfield Interceptor

Resplendent in blue and chrome, this 736cc parallel twin was Royal Enfield’s answer to the American market. With 53hp and a top speed of 168kph, it was a gentleman’s missile, larger than its 650cc British rivals and proud of it.

1925 Bohmerland (with sidecar)

One of the longest motorcycles ever built, this yellow-and-red marvel was designed by Albin Liebisch to seat three – plus a sidecar. Built in Czechoslovakia between 1924 and 1939, it features cast alloy wheels decades ahead of its time. This particular machine is the oldest known Bohmerland in existence.

1970 Indian Enfield 750

A rare hybrid of British engineering and Italian flair, this twin-cylinder beauty gleams in light blue and cream. Commissioned by Floyd Clymer (who owned the ‘Indian’ motorcycle marque’s name at the time) in a bold attempt to resurrect that brand by way of a new Indian twin, it features a Royal Enfield motor in a Tartarini-built chassis. However, before the project could go underway, Clymer died and the company ceased trading. Only 10 were ever made, and this one feels like a survivor from an alternate timeline.

1944 Harley-Davidson Model U (US Navy)

Painted in white with yellow saddlebags and a rifle scabbard, this military Harley was used for shore patrol during WWII. Of the 18,000 motorcycles Harley built for the military, only 366 were 1944 models. It could carry 350 rounds of .45 caliber ammunition, and a whole lot of history.

1954 BSA B34 Alloy Clipper

Often mistaken for the high-performance Gold Star, this export version of the B34 trails model was sold in the US for trail riding. With modest power and small fin alloy cylinders, it’s a quiet achiever: understated, rugged and very British.

1960 Vyatka VP 150

A Soviet scooter with a cheeky past, it’s essentially an unlicensed copy of the Italian Vespa. Painted in cheerful cream and blue, it’s a Cold War commuter with a warm heart. Roughly 3,00,000 were churned out behind the Iron Curtain, proving that two-wheeled freedom knows no borders.

1988 BMW K 100 RT & 1989 BMW R 80

These two well-worn BMWs aren’t just museum pieces, they’re global veterans. In 1990, investor-turned-adventurer Jim Rogers and his companion Tabitha Estabrook rode them across six continents, covering over 65,000 miles (over 1 lakh km) in 22 months. Rogers chronicled the journey in his book Investment Biker, a tale of grit, markets, and motorcycling that earned two Guinness World Records.Tabitha’s R 80, a street bike not built for deep sand or snowdrifts, endured terrain that would challenge modern adventure machines. The bikes remain in original condition, map still affixed, saddlebags still dusty, as if waiting for the next border crossing.

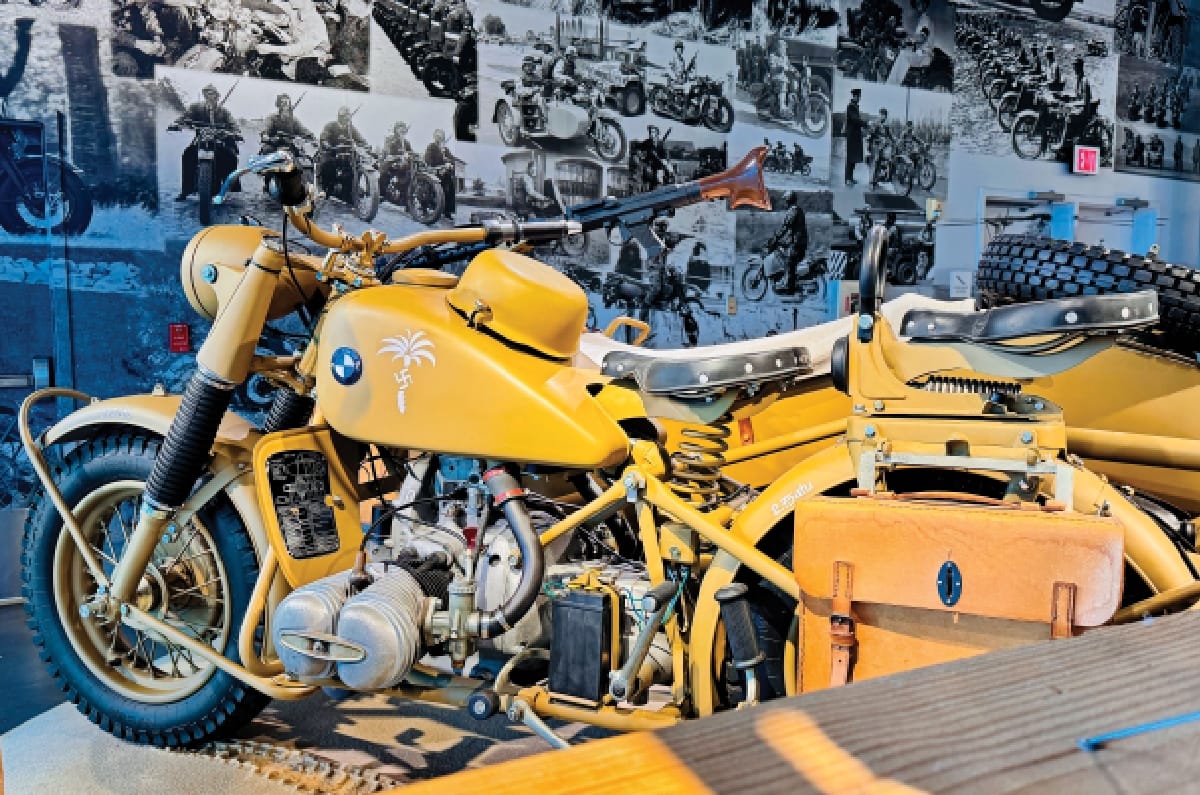

1943 BMW R75 3x2 (Afrika Korps)

Painted in desert yellow and built like a tank on two wheels, this WWII-era BMW was designed to tow light artillery but proved so powerful it lifted its own front wheel off the ground. With a Steib sidecar, reverse gears and optional sidecar wheel drive, it was a go-anywhere machine – rugged, overbuilt and unmistakably German.

Armed with a mobile machine gun and marked with the palm tree insignia of Rommel’s Afrika Korps, this motorcycle wasn’t just transport. It was strategy on wheels. Despite costing twice as much as the Porsche-designed VW military vehicle, over 16,000 were built and served throughout the war.

A fortuitous coincidence

I arrived at the Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum on October 4, 2025, expecting a quiet, slow wander among polished metal and retired ambition. Instead, I stepped straight into the Barber Vintage Festival, running from the 3rd to the 5th, and any hope of solitude vanished cheerfully.

The grounds had transformed. Motorcycles stood everywhere, immaculate or gently disreputable, all clearly cherished. The air carried fuel, hot oil, leather and food smoke. Engines fired without apology. A race bike screamed past in the distance. The museum had become less a sanctuary,more a gathering. Loud, friendly,alive. Even old motorcycles were doing what they were built to do, being worked hard rather than admired politely. For me, the true highlight was seeing Kenny Roberts in the flesh. I had watched him in the Seventies on a monochrome TV, defying the laws of physics on his legendary Yamaha YZR500, with its “speed block” livery created by the iconic Rollin ‘Molly’ Sanders. To stand a few metres away from him was pure ecstasy. That alone made my visit worthwhile and was the high point of my trip to the United States.

What began as a museum visit became something richer. A reminder that the road sometimes adds its own footnotes.

Plan a visit

The Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum stands at 6030 Barber Motorsports Parkway, Birmingham, Alabama, and is home to the world’s largest motorcycle collection, as certified by Guinness World Records. It is open daily (except major holidays) from 10am (12 noon on Sundays), to 6pm from April to September, and to 5pm from October to March. Admission is refreshingly modest at $20 for adults, with discounts for children, seniors and military visitors. It is truly a small price for the motorcycling feast on offer. If you can time a visit with a racing event at the adjoining circuit, you’ll witness the full vision: history preserved inside, and history being made outside, engines echoing across the Alabama hills.

from Autocar India https://ift.tt/sAN205x

Comments

Post a Comment